The 1849 Escape

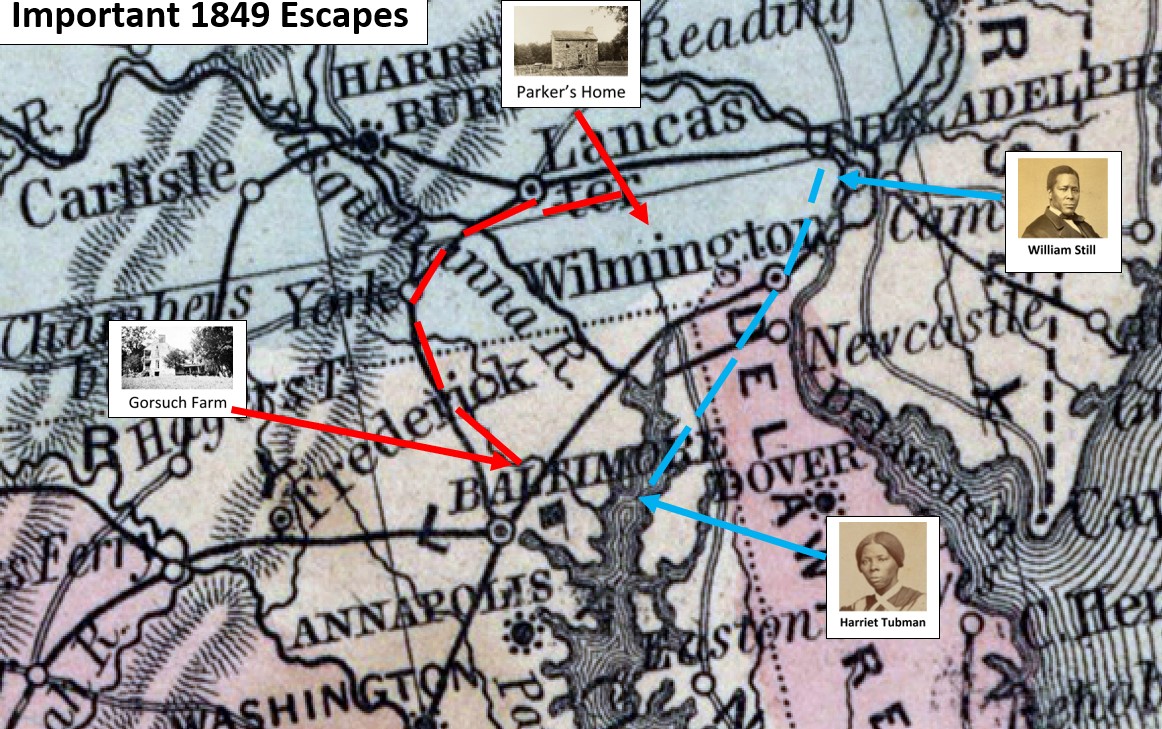

Historian Fergus Bordewich estimates that tens of thousands of American slaves escaped from bondage (Bound for Canaan p. 4). On November 6, 1849, four enslaved men escaped from Edward Gorsuch’s plantation in Maryland: Noah Buley, Nelson Ford, George Hammond and Joshua Hammond. We don’t know the details of their escape, but the men made it safely to Pennsylvania. Lancaster County was home to an active Underground Railroad led in part by William and Eliza Parker, a black couple. Bordewich describes the Underground Railroad as “the country’s first racially integrated civil rights movement” (Bound for Canaan p. 4). Yet, Lancaster also had slave-catchers, who helped Gorsuch find his runaways in 1851. Both sides relied on extensive secret communication. However, by the early 1850s, Parker’s organization was ready to send a new type of public message by fighting, not fleeing.

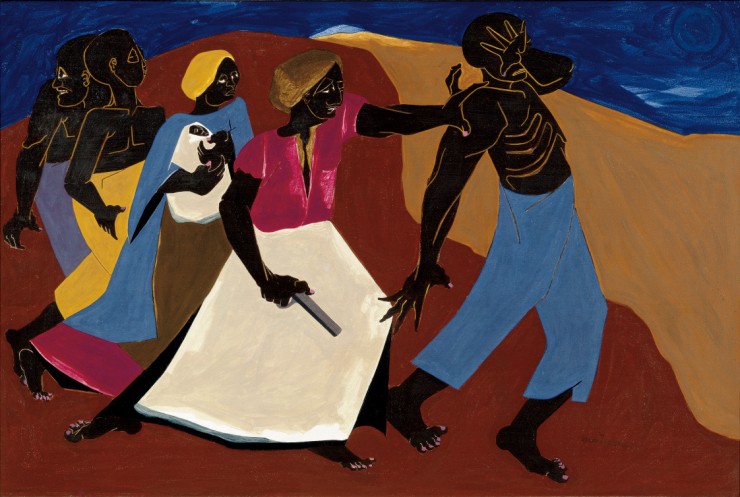

Freedom Seekers (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Timeline

1839: Maryland slave, William Parker, escapes to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.

1849: In October, Harriet Tubman escapes from Maryland with help from William Still and the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee.

1849: In November, four enslaved men escape from Edward Gorsuch’s plantation in Baltimore County, Maryland.

1851: Gorsuch receives information that his runaways are in Lancaster, protected by William Parker.

(1857 map from House Divided Project at Dickinson College)

Background

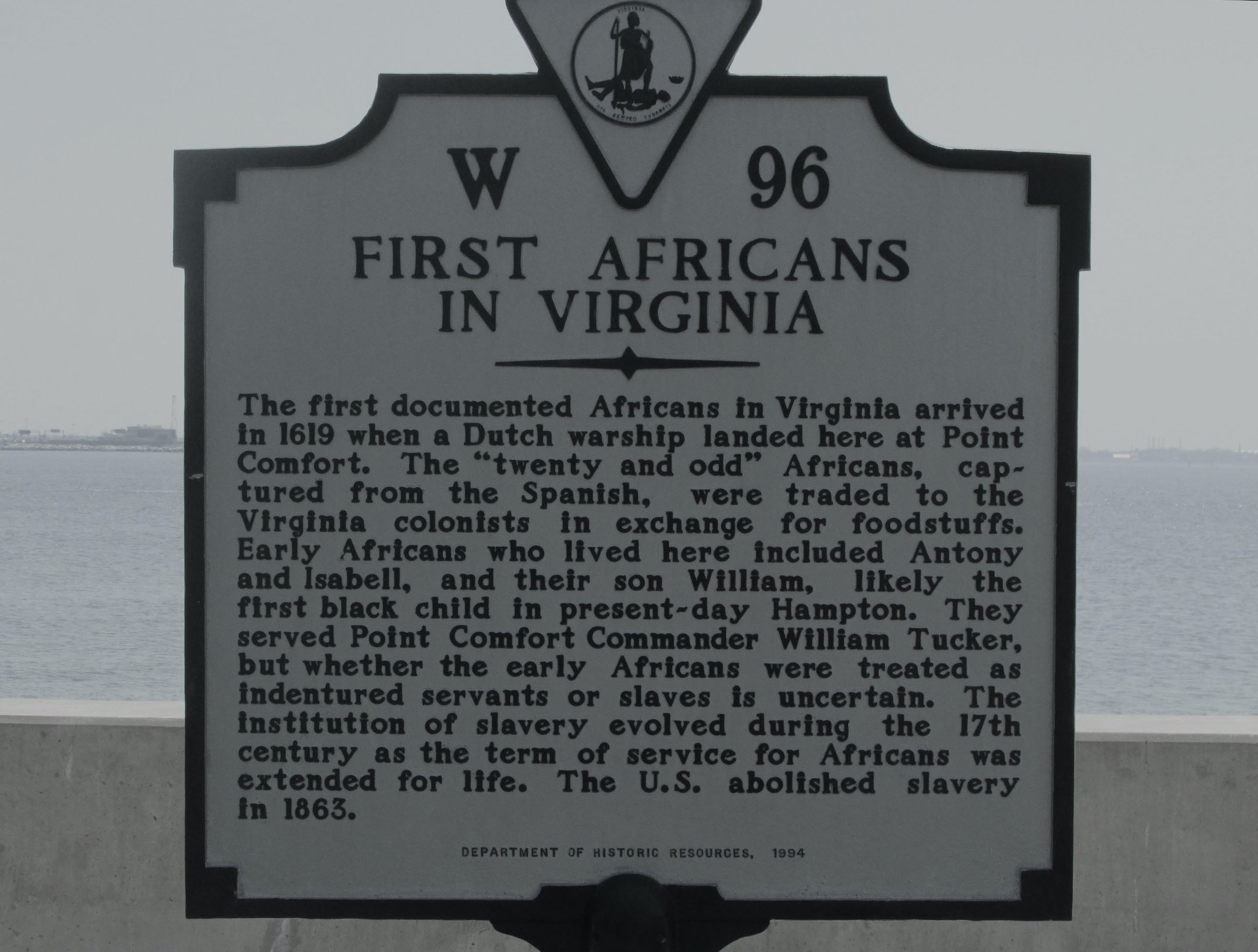

Upper South Slavery

(free.OPP)

Underground Railroad

(North Carolina Museum of art)

Freedom in Pennsylvania

Independence Hall (National Park Service)

Upper South Slavery

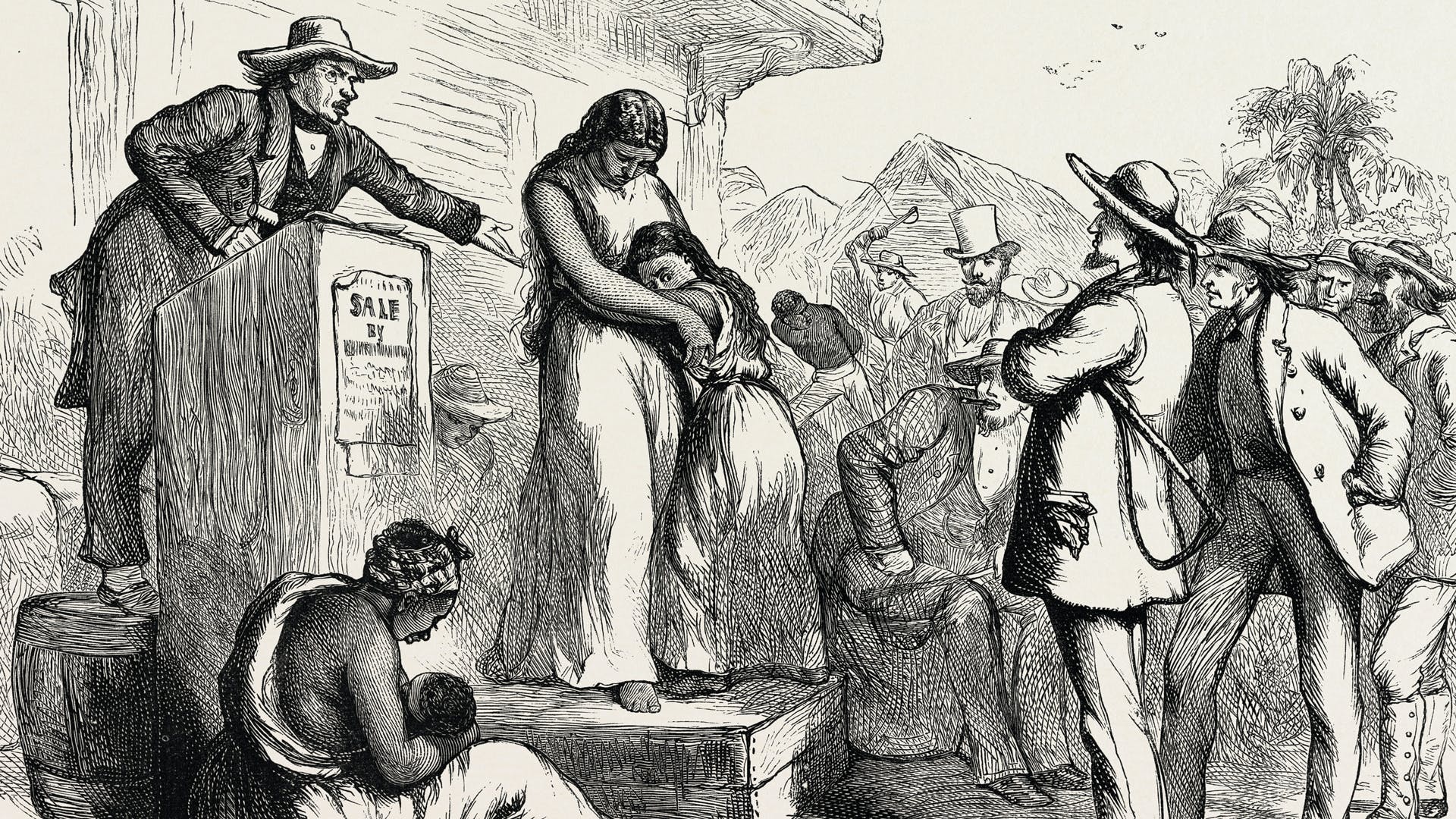

(history.com)

“[To the slaveholders] Slaves were a form of real estate, or human furniture, so to speak, whose personal life had no more intimate meaning than that of a cow, or a settee. Where they were considered human, the law allowed them no claim on their own families. It has been estimated that in the Upper South forcible separations probably destroyed one out of every three marriages by slaves, and that a similar proportion of enslaved children were taken away from one or both parents to be sold.”

--Fergus M. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan (2005), p. 23

(americainclass.org)

“Slave sales were a major source of income for Maryland planters. From 1820 to 1860, including the years of Parker's childhood, the state was in the midst of an economic and agricultural revival. Maryland was a major source of slaves for the economy of the lower south; the economy of Maryland depended on the sale of these surplus slaves.”

--Jonathan Katz, Resistance as Christiana (1971), p. 12-13

“Gorsuch was no Simon Legree. By all accounts, he did not beat his slaves… [though] Rumor had it among slaves that the master knew who took the grain. Nothing had been said yet, but they were waiting for the boot to drop.”

--Thomas P. Slaughter, Bloody Dawn (1991), p. 5, 9

Underground Railroad

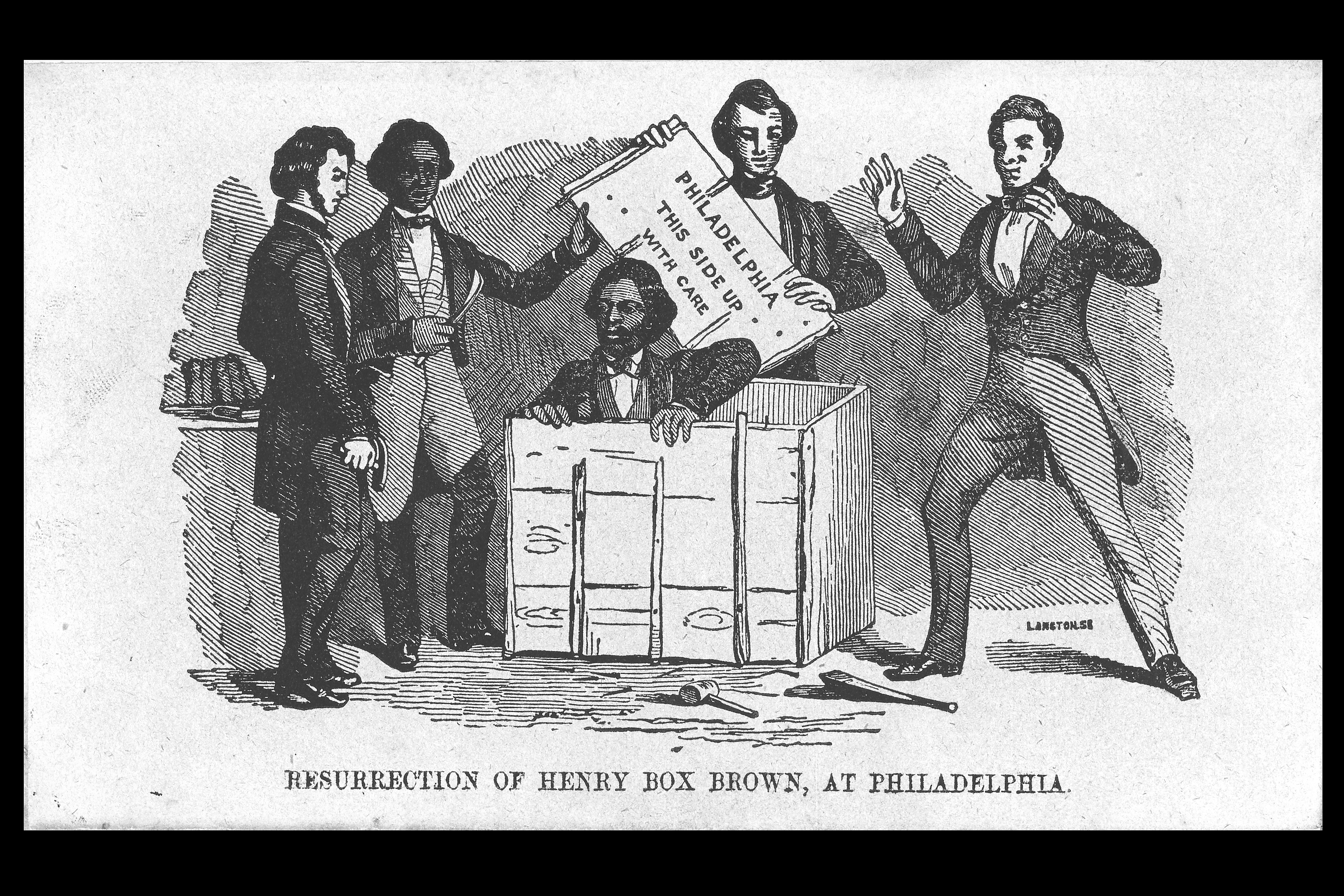

Henry "Box" Brown escaped in 1849 (UConn Today)

“But the Underground Railroad is no more ‘black history’ than it is ‘white history’: it is American history, and it swept into its orbit courageous Americans of every hue. It was the country’s first racially integrated civil rights movement, in which whites and blacks worked together for six decades before the Civil War, taking great risks together, saving tens of thousands of lives together, and ultimately succeeding together in one of the most ambitious political undertakings in American history.”

--Fergus M. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan (2005), p. 4

(History.com)

“In the late autumn of 1849 [Harriet Tubman] fled on her own. Although she was vague on the details, she later described her hundred-mile overland trek through eastern Maryland, and probably Delaware, as having been accompanied, phantasmagorically, by a pillar of cloud during the day, and a pillar of fire by night.

--Fergus M. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan (2005), p. 349

“It was November 6, 1849. Noah Buley, Nelson Ford, and George and Joshua Hammond talked quietly, and no doubt nervously, as they shoveled corn into the ox cart... We cannot know whether they ran simply because they feared the consequences of being discovered as thieves or whether stealing the grain was to raise money for an escape that they had planned all along. But run they did, with the help of Alexander Scott, "a tall yellow fellow," who was also one of Gorsuch's slaves.”

--Thomas P. Slaughter, Bloody Dawn (1991), p. 11

Freedom in Pennsylvania

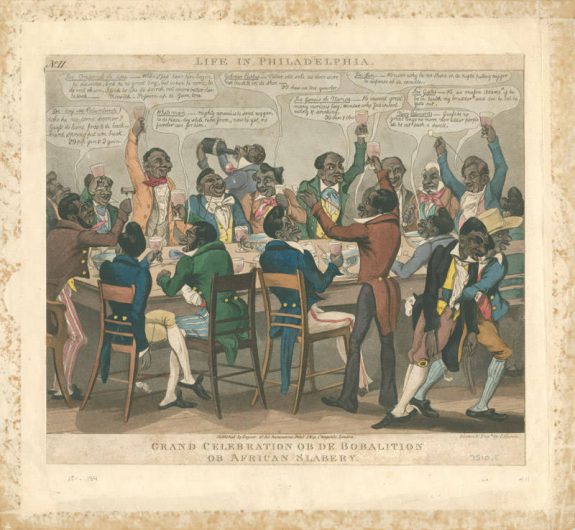

1833 image mocking free blacks (philadelphiaencyclopedia.org)

“Although freer than any of the slave states, the Pennsylvania into which William Parker had moved in the summer of 1839 was no utopia for black people. There was no slavery in Pennsylvania, but jobs open to blacks were generally the most menial and lowest paid. The jobs blacks had previously won were then being challenged by the competition of white immigrants pouring into America. Black Pennsylvania coal miners, canal and railroad workers lost their jobs to the newly arrived Irishmen who formed a cheap labor force.”

---Jonathan Katz, Resistance at Christiana (1971), p. 23

(wikipedia.org)

“The same person might be a Maryland slave under Maryland law and a Pennsylvania freeman under Pennsylvania law. Owners and agents, armed with Maryland authority to reclaim property, made theirs by Maryland law, were felonious kidnappers in Pennsylvania.”

--W.U. Hensel, The Christiana Riot and Treason Trials of 1851 (1911) p. 9.

Between 1765 and 1800, the number of free blacks in Philadelphia grew almost sixty-five times over, from 100 to 6,436, more than 9 percent of the city’s population.”

--Fergus M. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan (2005), p. 45

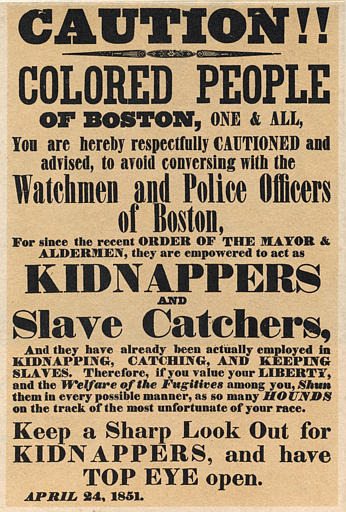

“Nowhere was a black person safe in America. Kidnapping was an omnipresent danger for free blacks, and fugitives could never feel secure, not even in the far northern cities of New England.”

--James Oliver Horton, "A Crusade for Freedom" in Passages to Freedom (2004) p. 182-183

“[William] Parker constituted the black self-defense organization in the Chester and Lancaster County area in 1841, ten years before the final incident in 1851.… In William Parker’s view, his self-defense organization’s motives were pure and justified. Parker’s association engaged in several resistance activities before the Christiana Resistance.”

--Ella Forbes, But We Have No Country (1998) p. 33-34

Primary Sources

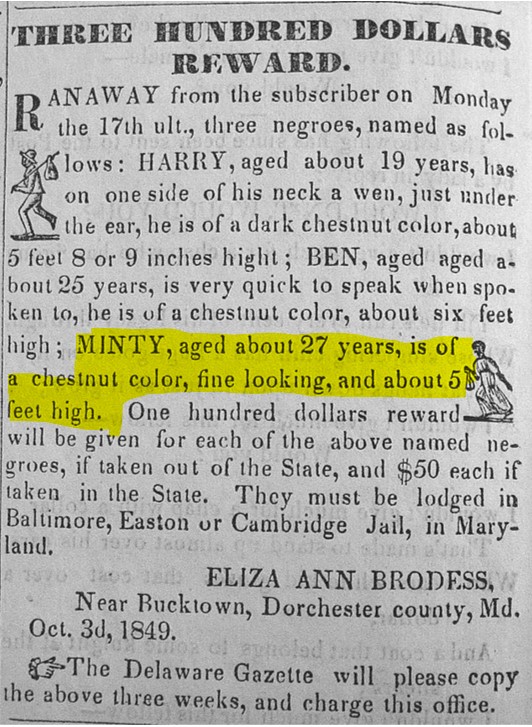

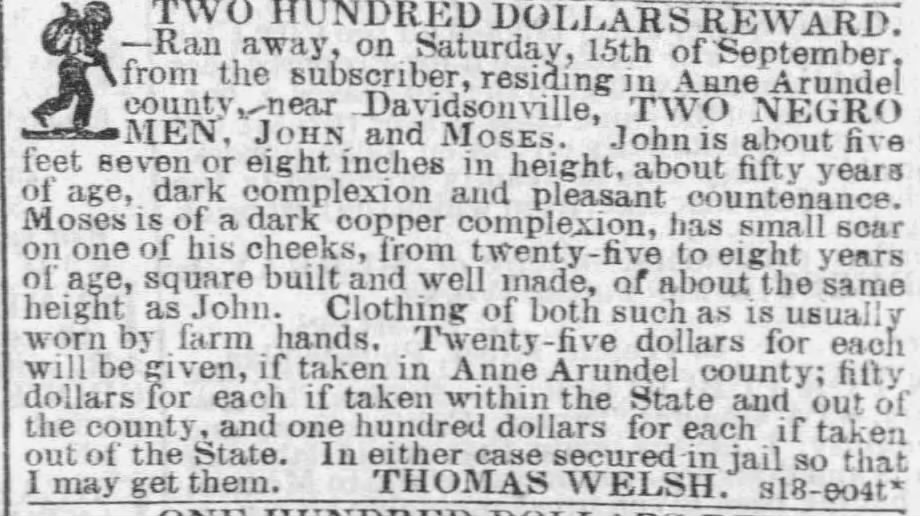

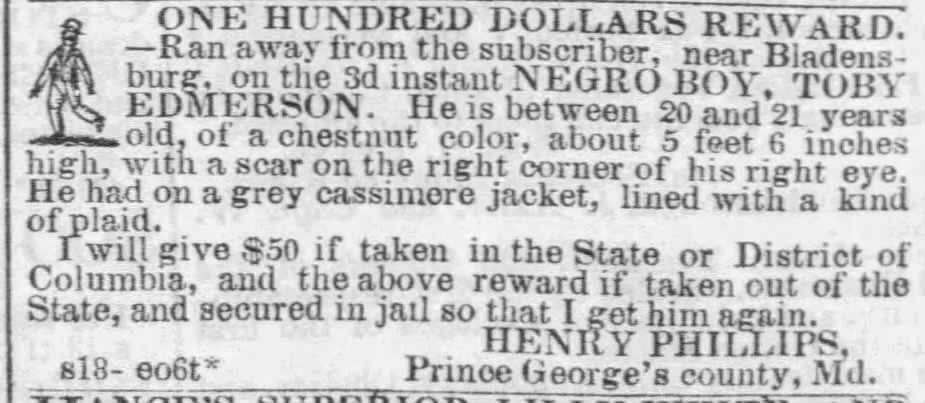

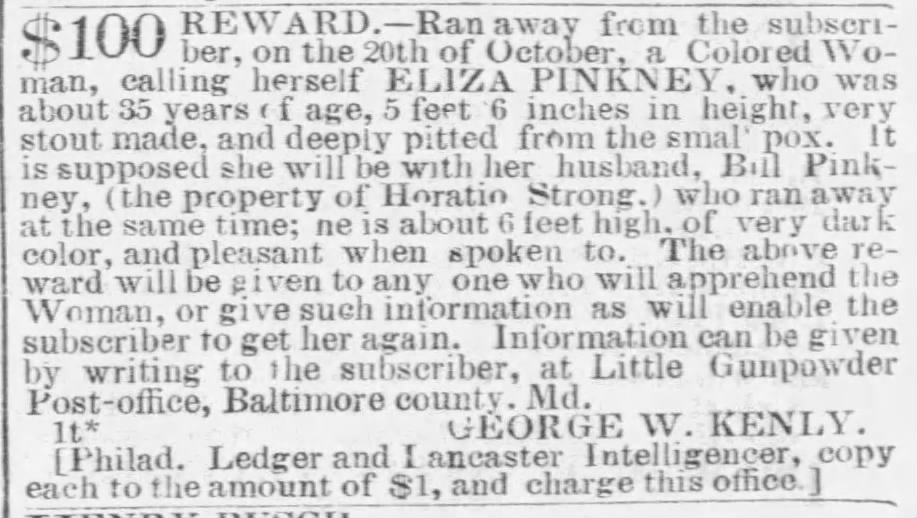

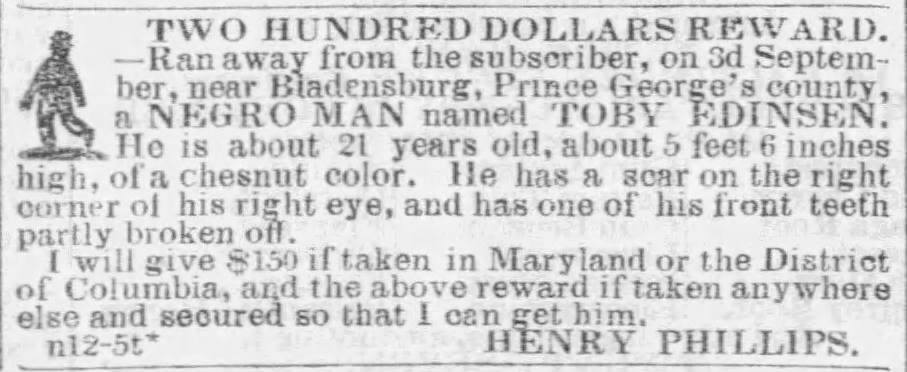

Runaway Slave Ads

We haven’t found Edward Gorsuch’s advertisement seeking his four runaways, but we know slaveholders communicated through these types of ads. Here are some examples of Maryland runaway slave ads from 1849, including one from Harriet Tubman’s owner.

Propaganda

Pro-Slavery

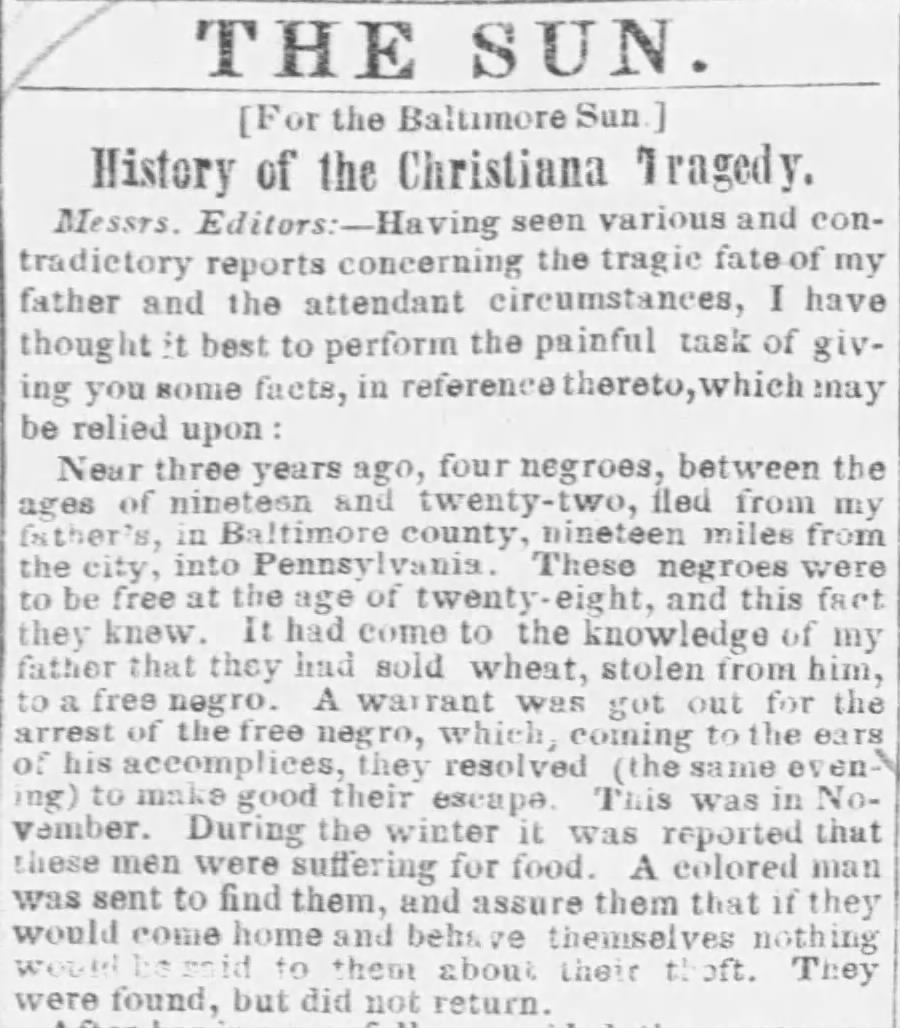

--John Gorsuch, Baltimore Sun, September 18, 1851

“Near three years ago, four negroes, between the ages of nineteen and twenty-two, fled from my father’s, in Baltimore county, nineteen miles from the city, into Pennsylvania. These negroes were to be free at the age of twenty-eight, and this fact they knew. It had come to the knowledge of my father that they had sold wheat, stolen from him, to a free negro. A warrant was got out for the arrest of the free negro, which, coming to the ears of his accomplices, they resolved (the same evening) to make good their escape.”

--John Gorsuch, Baltimore Sun, September 18, 1851

Anti-Slavery

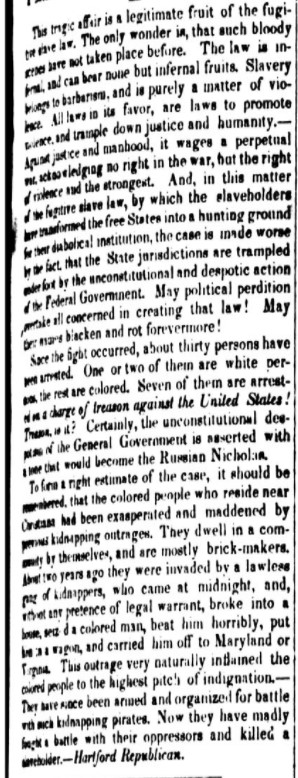

--The Liberator, September 26, 1851

“It should be remembered that the colored people who reside near Christiana had been exasperated and maddened by personal kidnapping outrages. They dwell in a community by themselves, and are mostly brick-makers. About two years ago they were invaded by a lawless gang of kidnappers, who came at midnight, and, without any pretense of legal warrant, broke into a home, seized a colored man, beat him horribly... ”

--The Liberator, September 26, 1851

UGRR Communication

The four Gorsuch freedom seekers ended up in Christiana under the protection of William and Eliza Parker and the local Underground Railroad --until a spy informed on them.

In the month of Sept, 1850, a colored man, known in the neighborhood around Christiana to be free, was seized and carried away by men known to be professional kidnappers, and has never been seen by his family since. In March 1851, in the same neighborhood, under the roof of his employer, during the night, another colored man was tied, gagged, and carried away, marking the road along which he was dragged by his own blood. No authority for this outrage was ever shown, and he has never been heard from. These and many other acts of a similar kind, had so alarmed the neighborhood that the very name of kidnapper was sufficient to create a panic. The blacks feared for their own safety, and the whites knowing their feelings, were apprehensive that any attempt to repeat these outrages would be the cause of bloodshed. Many good citizens were determined to do all in their power to prevent these lawless depredations, though they were ever ready to submit to any measures sanctioned by legal process. They regretted the existence among them of a body of people liable to such violence; but without combination, had, each for himself, resolved that they would do everything dictated by humanity to resist barbarous oppression.

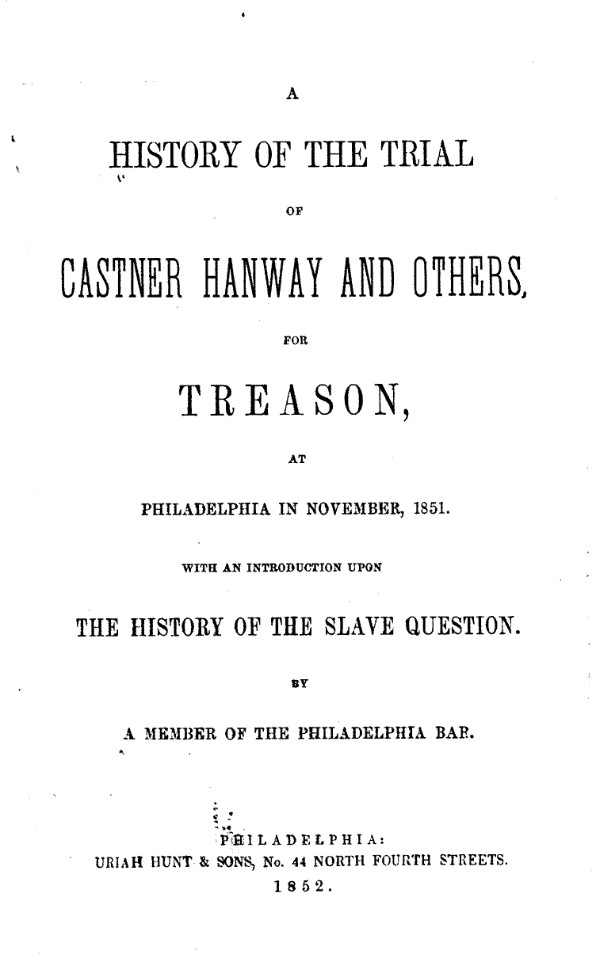

-- [W. A Jackson] A History of the Trial of Castner Hanway (1998) p.35-36

-- [W A Jackson] A History of the Trial of Castner Hanway (1998) p.35-36

Lancaster Co. 28 August 1851

Respected friend,

I have the required information of four men that is within two miles of each other. Now the best way is for you to come as a hunter disguised about two days ahead of your son and let him come by way of Philadelphia and get the deputy marshal John Nagle, I think his name is. Tell him the situation and he can get a force of the right kind it will take about twelve so that they can divide and take them all within half an hour. Now if you can come on & I will meet you at the gap when you get there. Inquire for Benjamin Clay’s tavern let your son and the marshal get out Kinyer’s hotel now if you cannot come at the time spoken of write very soon. And let me know when you can. I wish you to come as soon as possible.

Very respectfully thy friend

Wm. M.P.

--William Padgett to Edward Gorsuch, August 28, 1851, excerpted in Thomas P. Slaughter Bloody Dawn (1991) p. 19

Gorsuch Farm (gutenburg.org)

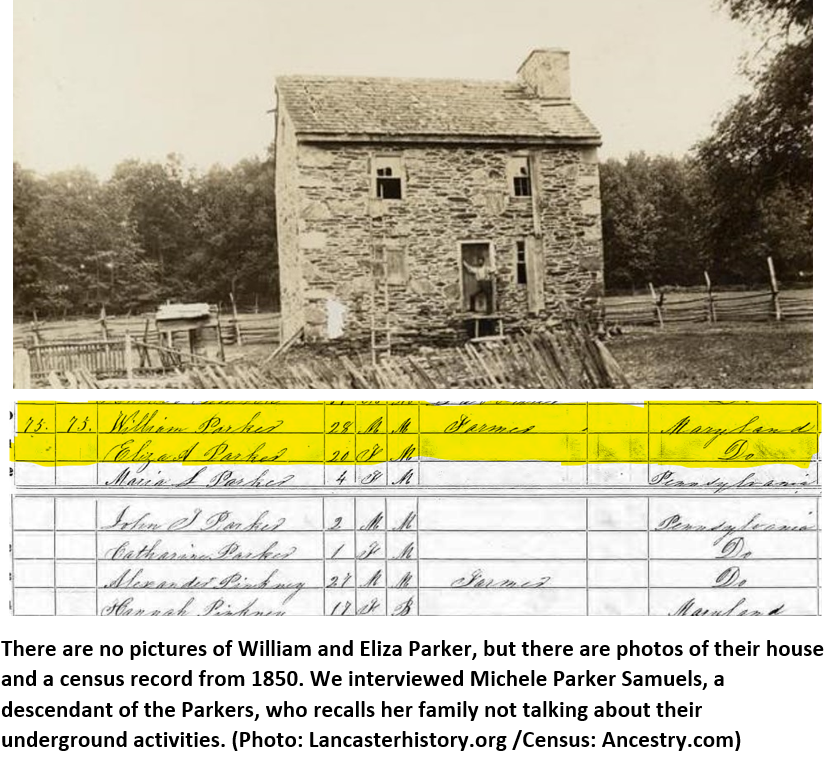

Parker Descendant Describes Family's UGRR Secrets

--Michele Parker Samuels, zoom interview, April 17, 2021