Christiana Resistance of 1851

On September 8, 1851, Edward Gorsuch went to Pennsylvania to recapture his four runaways under the new Fugitive Slave Law. Gorsuch's spy had warned him to expect resistance, so he brought a small armed posse. Meanwhile, William Parker had received a warning about slave-catchers. Gorsuch's party and the U.S marshal confronted Parker on the morning of September 11. Eliza Parker blew a horn and dozens of neighbors swarmed to help. This was their organized battle cry for freedom. By afternoon, Gorsuch lay dead, and his son severely wounded. Newspapers from around the country reported on the violence. Authorities arrested dozens, but Parker and others escaped, reaching Canada with help from Frederick Douglass.

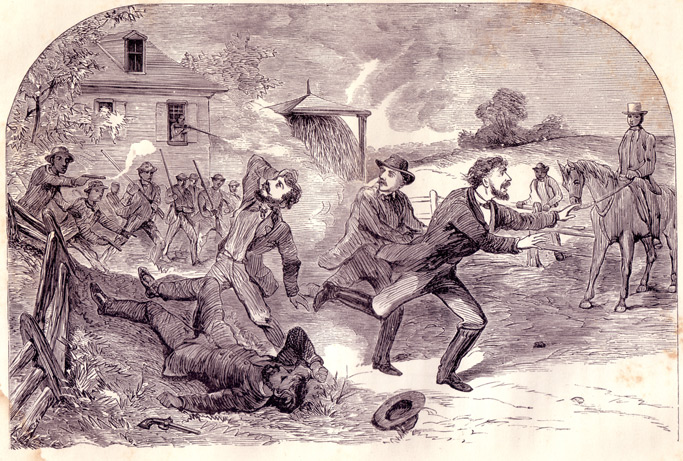

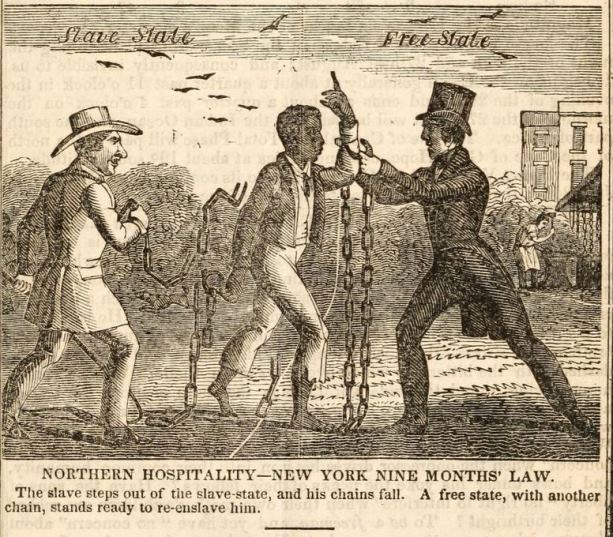

1872 illustration depicting Christiana Resistance (House Divided Project at Dickinson College)

Timeline

September 18, 1850: Congress passes the Fugitive Slave Law.

September 10, 1851: Gorsuch and federal officials set off to Christiana looking for his fugitives.

September 11, 1851 AM: The slave catching party arrives at William Parker’s house.

September 11, 1851 PM: After a confrontation that kills Gorsuch, Parker and others escape.

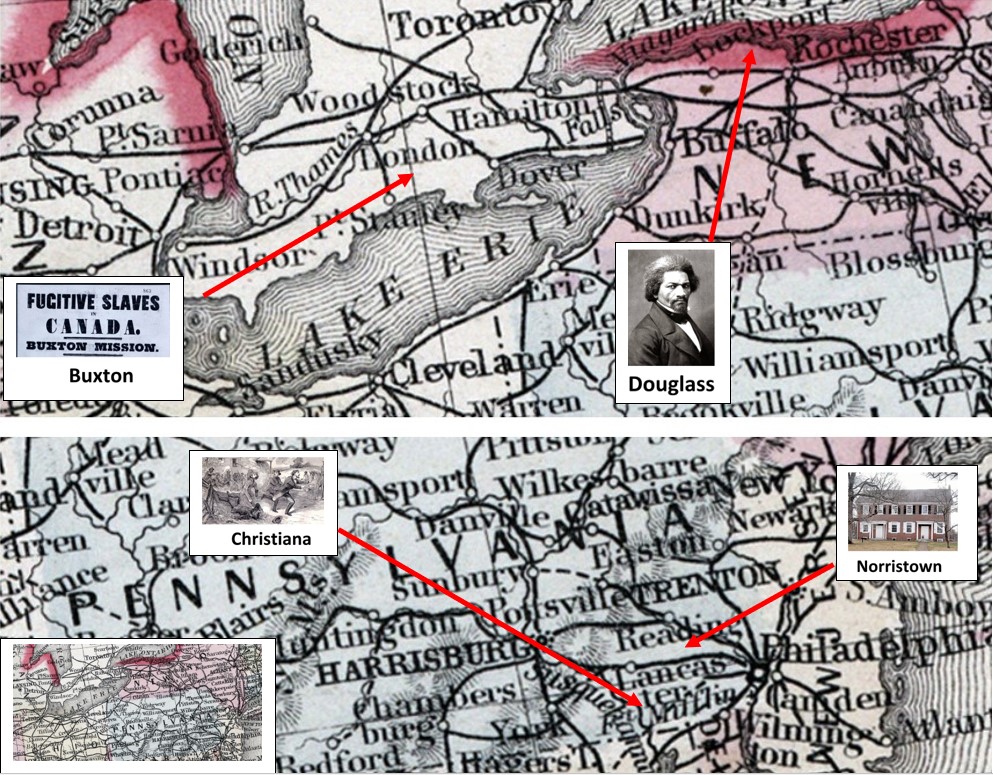

(Credit: 1857 map from House Divided Project at Dickinson College)

Background

Fugitive Slave Law

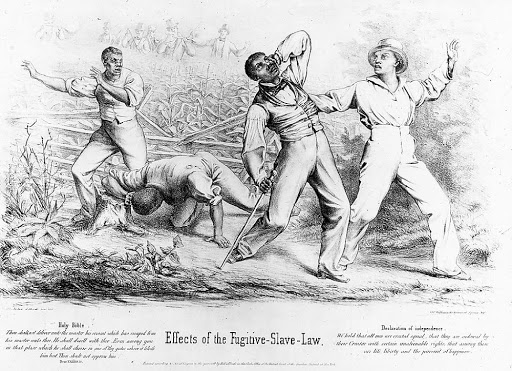

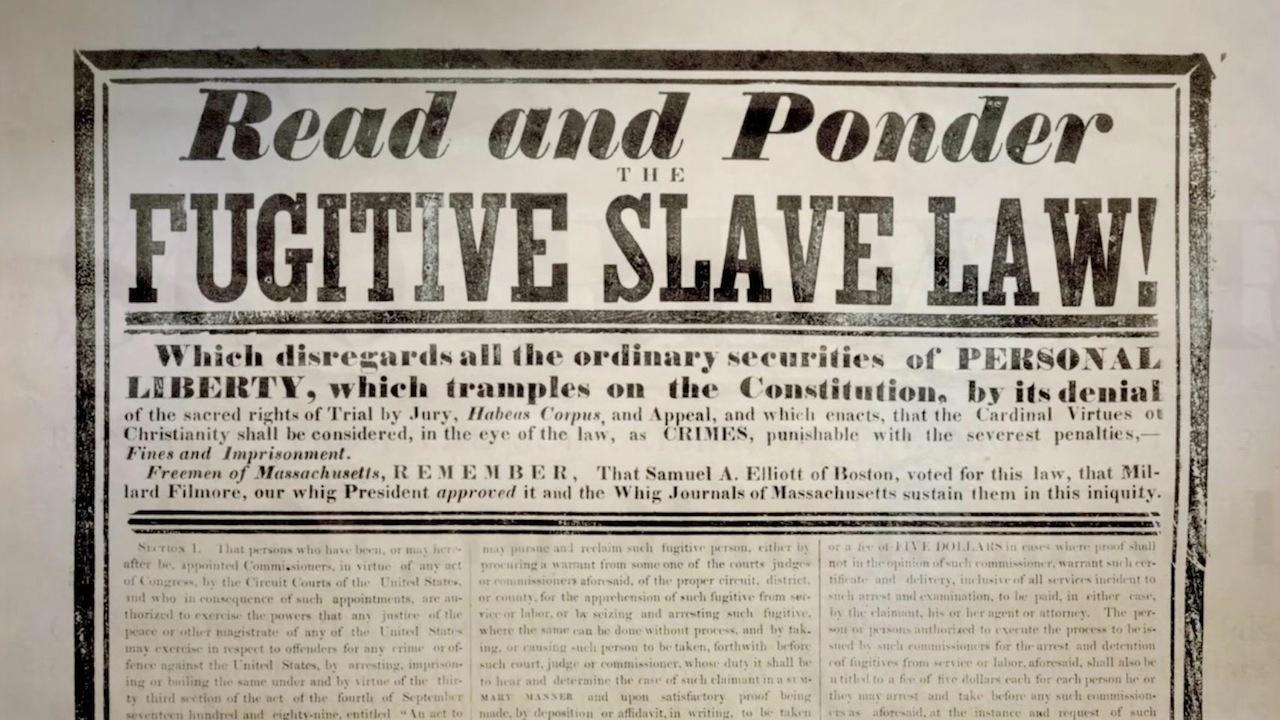

1850 illustration (nysed.gov)

William and Eliza Parker

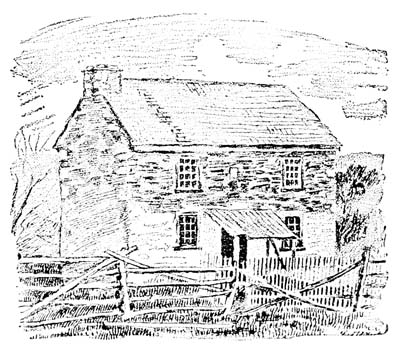

Parker's House (gutenberg.org)

Vigilance Committees

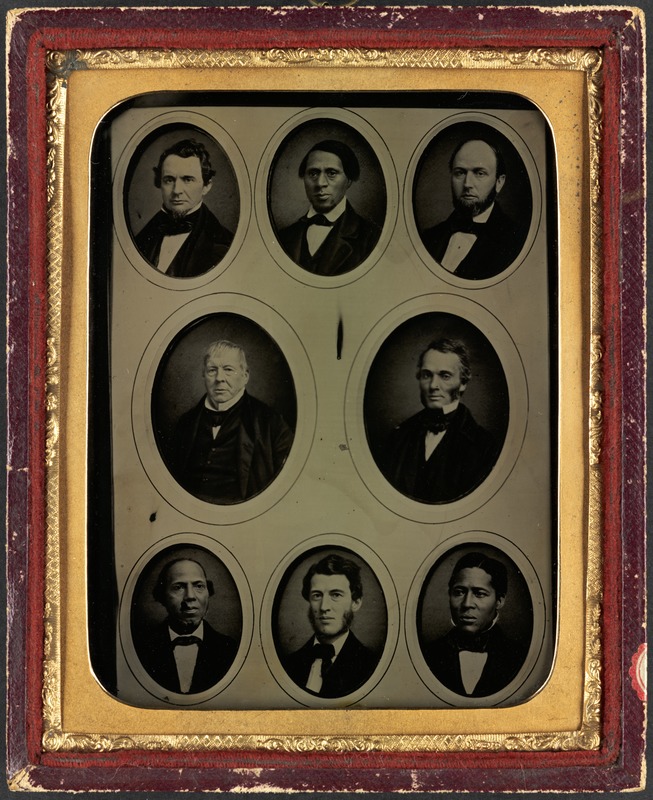

Philadelphia Vigilance Committee (digitalcommonwealth.org)

Fugitive Slave Law

(pbs.org)

“The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was considered inadequate to stem the flow of fugitive slaves and to curb the activities of friends of fugitives, the call for a stronger, enforceable law was a central slave state demand in the divisive sectional struggle that produced the Compromise of 1850. As a key element of the Compromise, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 criminalized active and passive assistance to fugitive slaves."

--J. Blaine Hudson, Encyclopedia of the Underground Railroad (2014) p. 5.

(conneticuthistory.org)

“[The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850] was comprehensive and draconian. Anyone who hindered a slave catcher, attempted the rescue of a recaptured fugitive, ‘directly or indirectly’ assisted a fugitive to escape, or harbored a fugitive, was liable to a fine of up to one thousand dollars and six months’ imprisonment, plus damages of one thousand dollars to the owner of each slave that was lost.”

--Fergus M. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan (2005), p. 319.

"The new Fugitive Slave Law tipped the balance of power in the battle for freedom toward the slave catchers, as it brought federal law-enforcement officials into the fray on the side of the masters. It was definitely going to be easier to retake fugitive slaves legally. No longer could Pennsylvania’s officials openly resist efforts to recover fugitives. No longer would masters be denied protection of the courts when they ventured north to recover their property. Despite several notorious examples of resistance, the law was being tolerated, even tacitly welcomed in Pennsylvania, as in most other Northern States.”

--Thomas P. Slaughter, Bloody Dawn (1991), p. 51

“On September 8, Edward Gorsuch took an express train to Philadelphia, as informer Padgett had suggested, coming to the city ahead of the rest of his party. In Philadelphia, Gorsuch went to see fugitive slave commissioner Edward D. Ingraham, and on September 9 obtained four fugitive slave warrants. Ingraham was one of the few men in Pennsylvania who had accepted a special commission under the new fugitive slave law.”

--Jonathan Katz, Resistance as Christiana (1971), p. 74.

William and Eliza Parker

Eliza Parker gravestone (thecookingladies.com)

“Parker, twenty-nine years old in 1851, was born a slave in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, and had escaped to Pennsylvania in 1842 by following the railway tracks from Baltimore to York. He had spent the intervening years working on farms in Lancaster County. In 1843, he underwent a transformative experience at an abolition rally where he listened raptly to an oration by Fredrick Douglass, whom he had known years earlier in Maryland as the simple slave Fredrick Bailey.”

--Fergus M. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan (2005), p. 327.

Parker's House (blackpast.org)

“In Pennsylvania, William Parker met and married young, dark-skinned Eliza Ann Elizabeth Howard, a fugitive from Maryland, whose ‘experience of slavery’ says Parker, ‘had been much more bitter than my own.’ Whatever the exact nature of this experience, it prepared Eliza to become a determined fighter when the slave hunters appeared."

--Jonathan Katz, Resistance as Christiana (1971), p. 29.

“According to Parker, when he returned home from work on Wednesday evening, September 10, Samuel Thompson and Joshua Kite were waiting for him. Also, there that evening were Parker’s wife Eliza; Eliza’s sister Hannah and her husband, Alexander Pinckney; and Abraham Johnson, a fugitive from Cecil County, Maryland, all of whom lived in the house. Thompson, Kite and the rest of the household were in an uproar about the rumor concerning kidnappers. ‘I laughed at them,’ Parker recalled, ‘and said it was all talk… They stopped for the night with us, and we went to bed as usual.’

--Thomas P. Slaughter, Bloody Dawn (1991), p. 57

Vigilance Committees

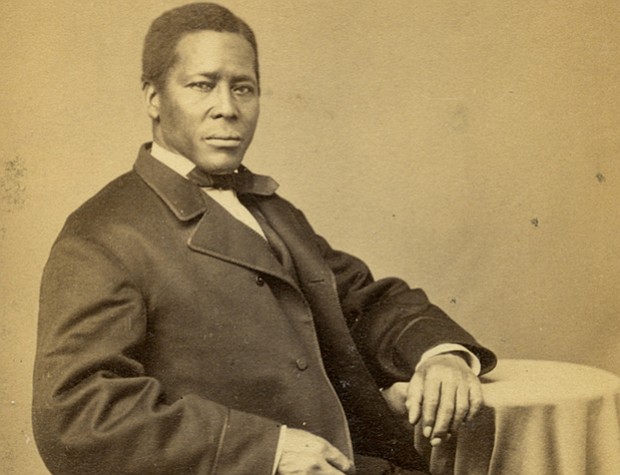

William Still, Philadelphia Vigilance (kpbs.org)

“The likelihood of pursuit and recapture diminished as fugitive slaves moved farther north. Under such conditions, the Underground Railroad seldom, ‘ran underground,’ in these areas and, at least before 1850, friends of the fugitive operated through local vigilance societies, and anti-slavery networks…”

--J. Blaine Hudson, Encyclopedia of the Underground Railroad (2014) p. 4.

Boston Vigilance headquarters (nps.org)

“The Committee of Vigilance and Safety formed at a Boston meeting in October 1850 was modeled after the Vigilance Committee established in 1846. The Philadelphia Vigilance Committee took its cue from the activities of an earlier organization, as did the New York Vigilance Committee, which had its first incarnation in the work of David Ruggles and others in 1835…”

--R.J.M. Blackett, "Freeman to the Rescue" In Passages to Freedom (2004) p. 136-137

“William Parker led this self-protection organization. He was a man of courage, intelligence, bravado, and justifiable pride, who was admired by Lancaster’s black residents, and some of its whites, and rightly feared by those who wished ill to him and his cause.”

--Thomas P. Slaughter, Bloody Dawn (1991), p. 47.

Primary Sources

Propaganda

Pro-Slavery

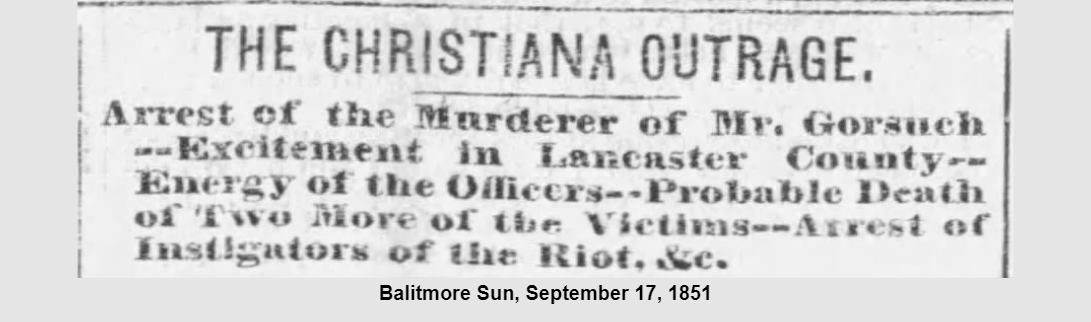

Baltimore Sun (Reprinted in Poughkeepsie Journal, New York) September 20, 1851

“The runaways, with some negroes of the place had taken refuge in a home and on the U.S. Marshal with his posse, in company with the above named persons approached the house, the negroes sallied from the house and fired upon them, killing Mr. Edward Gorsuch instantly, and mortally wounding his son, from which he afterwards died. Mr. Nelson and Mr. Hutchins were also severally injured; the other it is said, escaped unhurt. The Marshal’s party then fired upon the negroes, and it is said, killed four of them. At the time of making the sally, one of the negroes struck the corpse of the elder Mr. Gorsuch with an axe, splitting his skull open.”

--Baltimore Sun (Reprinted in the Poughkeepsie Jounral, New York) September 20, 1851

Anti-Slavery

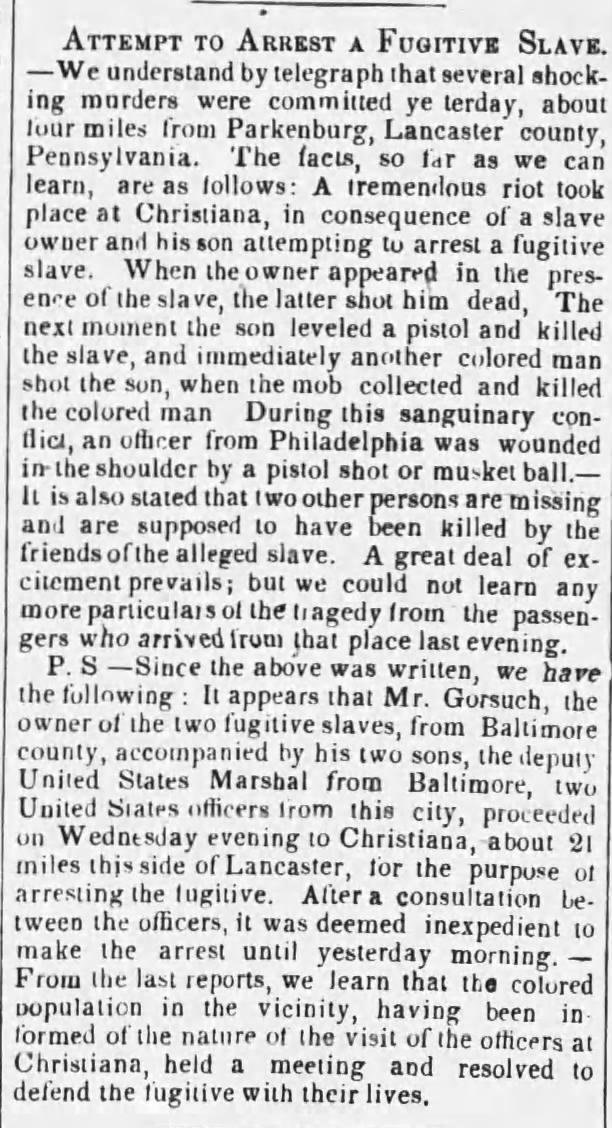

(Buffalo, New York) The Advocate September 18, 1851

“A tremendous riot took place at Christiana, in consequence of a slave owner and his son attempting to arrest a fugitive slave. … From the last reports, we learn that the colored population in the vicinity, having been informed of the nature of the visit of the officers at Christiana, held a meeting and resolved to defend the fugitive with their lives.”

--(Buffalo, New York) The Advocate September 18, 1851

Parker's Account of the Resistance

"By this time day had begun to dawn; and then my wife came to me and asked if she should blow the horn, to bring friends to our assistance. I assented, and she went to the garret for the purpose. When the horn sounded from the garret window, one of the ruffians asked the others what it meant; and Kline said to me, "What do you mean by blowing that horn?"

I did not answer. It was a custom with us, when a horn was blown at an unusual hour, to proceed to the spot promptly to see what was the matter. Kline ordered his men to shoot any one they saw blowing the horn. There was a peach-tree at that end of the house. Up it two of the men climbed; and when my wife went a second time to the window, they fired as soon as they heard the blast, but missed their aim. My wife then went down on her knees, and, drawing her head and body below the range of the window, the horn resting on the sill, blew blast after blast, while the shots poured thick and fast around her. They must have fired ten or twelve times. The house was of stone, and the windows were deep, which alone preserved her life"

--William Parker. “The Freedman’s Story Part 1&2.” The Atlantic. February, 1866.

William Parker's House (psu.edu)

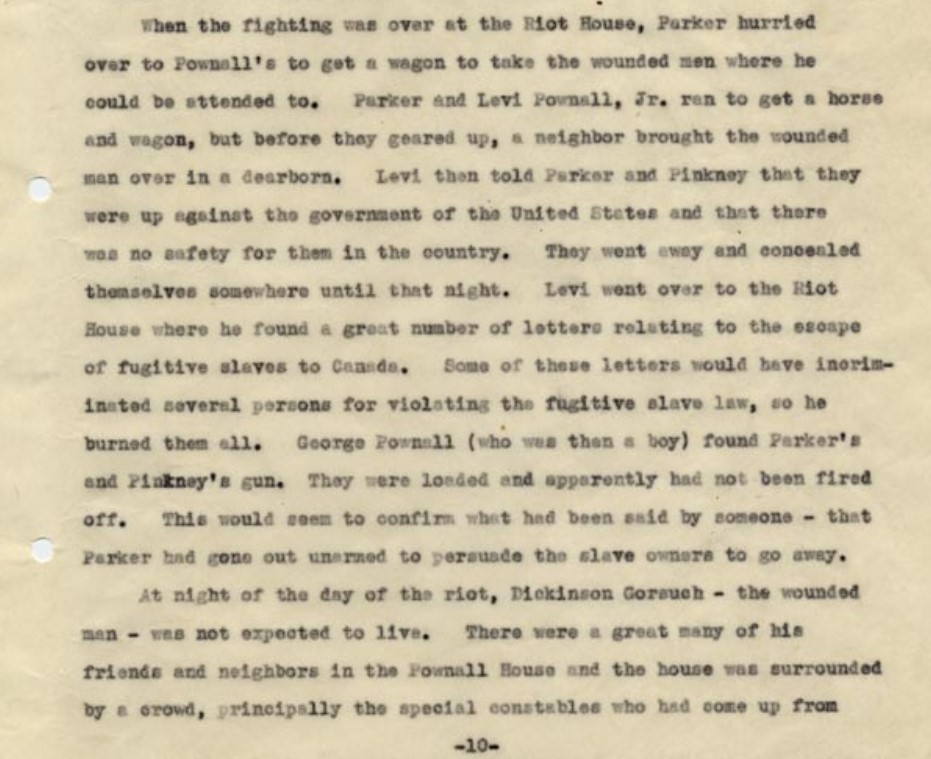

Neighbor's Recollection of Parker's Escape

“Levi then told Parker and Pinckney that they were up against the government of the United States and that there was no safety for them in the country. They went away and concealed themselves somewhere until that night.”

--"Some Recollections of a Long and Unsuccessful Life," by George Steele. 1918, unpublished (Lancasterhistory.org).

(Citation: "Some Recollections of a Long and Unsuccessful Life," by George Steele. 1918. upublished (Lancasterhistory.org).

Historian Calls Horn-Blowing Part of Resistance Communication "System"

Image Credit; Smithsonian // Zoom interview Fergus Bordewich, Ferbruary 25, 2021, Horn and video credit; Aiden Pinsker